Dengue of Arthropod-Borne Viruses Infection

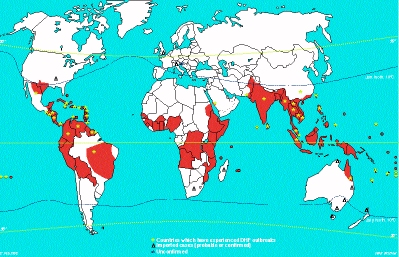

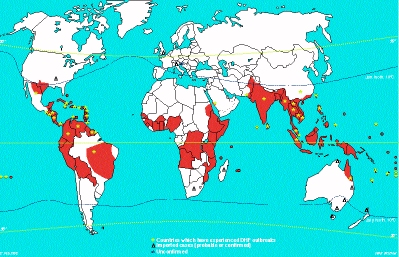

Hundreds of thousands of cases of dengue occur every year in

endemic and epidemic forms in tropical and subtropical areas of

the world. The attack rates during epidemics can reach as high as

50%. Dengue is a prevalent public health problem in SE Asia, the

Caribbean, Central America, Northern South America and Africa.

(See red coloured areas in map below). In hyperendemic areas,

most cases occur in young children as the majority of the

population had already been infected with multiple serotypes. In

other areas, older children and adults are more likely to be

affected. Maximum number of cases occur during the months of the

year with the highest rainfall and temperatures, when Aedes

aegypti populations are at their highest. A. aegypti mosquitoes

deposit their eggs in waterfilled containers and thus

reproduction is highest during periods of high rainfall.

4 serologically distinguishable types of dengue are recognized (DEN 1-4). The vector mosquito becomes infected by feeding on a viraemic host. The virus becomes established in the salivary glands of the mosquito from where it can be transmitted to susceptible individuals. Following an incubation period of 2 to 7 days, the virus is disseminated (route unknown), to the organs of the RE system (liver, spleen. bone marrow and lymph nodes). other organs may be involved such as the heart, lungs and GI tract.

a. Clinical Manifestations

The clinical presentation of dengue in children is varied. The disease may be manifested as an undifferentiated febrile illness, an acute respiratory illness, or as a GI illness: atypical presentations which may not be recognized by clinicians as dengue. Older children and adults infected with dengue the first time will display more classical symptoms: sudden onset of fever, severe muscle aches, bone and joint pains, chills, frontal headache and retroorbital pain, altered taste sensation, lymphadenopathy, and a skin rash which appears 3 days after the onset of fever. The rash may be maculopapular, petechial or purpuric and is often preceded by flushing of the skin. Other haemorrhagic manifestations may be seen such as epitaxis, gingival bleeding, ecchymoses, GI bleeding, vaginal bleeding and haematuria. Severe cases of bleeding should not be diagnosed as Dengue haemorrhagic fever (DHF) or Dengue shock syndrome (DSS) unless they meet the criteria below.

DHF or DSS are usually seen in children and usually occurs in 2 stages. The first milder stage resembles that of classical dengue and consists of a fever of acute onset, general malaise, headache, anorexia and vomiting. A cough is frequently present. After 2 to 5 days, the patient's condition rapidly worsens as shock begins to appear. Haemorrhagic manifestations ranging from petechie and bleeding form the gums to GI bleeding may be seen. An enlarged nontender liver is seen in 90% of cases. The WHO recommended the following criteria for the diagnosis of DHF and DSS:

1. Fever

2. Haemorrhagic manifestations including at least a positive

tourniquet test.

3. Enlarged liver

4. Shock

5. Thrombocytopenia (<=100,000 ul)

6. Haemoconcentration (HcT increased by =20%)

A diagnosis of DSS is made when frank circulatory failure is

seen, and occurs in one third of cases of DHF. DHF has been

graded by the WHO on the basis of its severity.

| Grade I Grade II Grade III Grade IV |

Fever accompanied by

non-specific constitutional symptoms, the only

haemorrhagic manifestation is a positive tourniquet

test Spontaneous bleeding in addition to the manifestations of Grade I patients, usually in the form of skin and/or other haemorrhages Circulatory failure manifested by rapid and weak pulse, narrowing of pulse pressure (20 mmHg or less) or hypotension, with the presence of cold clammy skin and restlessness Profound shock with undetectable blood pressure and pulse |

| Grade III and Grade IV DHF are also considered as Dengue Shock Syndrome. |

b. Immunology

The immunological response to dengue infection depends on the individual's past exposure to flavivirus. The flavivirus group shares cross-reacting antigen(s). Primary infection results in the production of antibodies against the infecting serotype predominantly. Reinfection with another dengue serotype (or other flaviviruses) usually produces a secondary (heterotypic) response characterized by very high titres to all 4 dengue virus serotypes and other flaviviruses, so that serological identification of the infecting agent is quite difficult if not impossible. After a first infection with one dengue serotype, cross-immunity to other serotypes may persists for a few months, but after 6 months, reinfection with another serotype may occur.

c. Pathology

There are 2 theories proposed for the pathogenesis of DHF and DSS: virus virulence and immunopathological mechanisms. The weight of the available evidence supports the immunopathological theory. DHF and DSS occurred most often in patients with a secondary (reinfection) serological response. However, the observation that DHF and DSS occurred in infants with a primary response cast some doubt on this theory until it was demonstrated that preexisting maternal antibody had a similar effect to acquired antibody. The antibody-dependent theory proposes that in the presence of non-neutralizing heterotypic antibody (whether maternally derived or not) to dengue, virus-antibody complexes are formed which are more capable of infecting permissive mononuclear phagocytes than uncomplexed dengue virus.

d. Laboratory Diagnosis

1. Serology - HI, CF and PRN tests are commonly used. The high degree of cross-reactivity between flaviviruses can make the interpretation of serological results very difficult.

2. Virus isolation - this can be accomplished by the intracerebral inoculation of sera from patients into suckling mice. Sera can also be inoculated intrathoracically into Aedes mosquitoes. Head squash preparations are examined for the presence of antigen by the FA technique. Cell cultures such as LLC MK-2 and several mosquito-derived cell lines can be used.

e. Treatment and Prevention

There is no specific antiviral treatment available. Management

is supportive and intensive medical management is required for

cases of severe DHF and DSS. No vaccine for dengue is available

but a tetravalent live-attenuated vaccine has been evaluated in

Thailand with favourable results. Scale-up preparation for

commercial production of the vaccine is underway and it is

anticipated that the vaccine will become available soon and

evaluated in large scale clinical trials. To avoid dengue,

travelers to endemic areas should avoid mosquito bites.

Prevention of dengue in endemic areas depends on mosquito

eradication. The population should remove all containers from

their premises that may serve as vessels for egg deposition.

Vector surveillance is an integral part in control measures to

prevent the spread of dengue outbreaks. Regular inspections as

part of law enforcement may be used in the control of mosquito

vectors. The object of source reduction is to eliminate the

breeding grounds in and around the home environment, construction

sites, public parks, schools and cemeteries. Illegal dumping of

household refuse provide favorable breeding sites for mosquitoes.

Long-term control should be based on health education and

community participation, supported by legislation and law

enforcement. Domestic water supplies should be improved in order

to reduce the use of containers for the storage of water.

ORBIVIRUSES

Orbiviruses are insect-borne viruses primarily of veterinary importance. Orbiviruses contain dsRNA arranged in 10 segments except for the members of the Colorado tick fever serogroup which have 12 segments of dsRNA. They vary in size from 50 to 90nm with 92 capsomers. The capsid is a double-layered protein. The outer coat is diffuse and unstructured while the inner layer is organized in pentameric-hexameric units. Colorado tick fever is caused by a virus belonging to the family of Reoviridae. It is a zoonotic disease of rodents and is transmitted to man via tick bites. It is prevalent in the Rocky Mountains and more western regions of the USA. It is a dengue-like illness albeit with a relatively low incidence. Colorado annually reports 100 to 300 cases but the disease is underreported there and from other western states as well. There is a strong seasonal trend with the majority of cases occurring between February and July. Chipmunks and squirrels serve as amplifying hosts.

Following an incubation period of 3 to 6 days, a high fever of acute onset is seen, along with chills, joint and muscle pains, headache, N+V. A maculopapular rash may be seen in a minority of patients. A more severe clinical picture may be seen in children, who may develop haemorrhagic manifestations including severe GI bleeding and DIC. Aseptic meningitis or encephalitis may be seen. CTF may be diagnosed by virus isolation whereby the patient's blood is inoculated into suckling mice or cell culture lines such as Vero, followed by identification by IF, N or CF tests. More rapid diagnosis can be made by performing IF directly on the blood clots. A IgM tests as well as other serological techniques are available for serological diagnosis. No licensed vaccine for CTF is available nor is it practicable because of the rarity and the benign nature of the disease. Public health education remains the most preventative measure.